Reclaiming Creativity: The Sandbox of Infinite Possibilities

A Fort, a Mess, a Mindset: What Children Know About Creativity That We Forgot

Chapter 5

A Return to the Sandbox: Where Dragons Need Bigger Doors and Ideas Get to Be Messy

There’s a brief, golden chapter in life, before report cards, performance reviews, and that dreaded voice in our heads…when we still believe in magic.

A time when a spoon was a spaceship. The bed was lava. Dragons lived behind couch cushions. When failure wasn’t a threat.

When nothing had to be perfect to be possible.

I saw that chapter alive again in my niece Eva. Every time she plays in her imaginative world of magical creatures, it comes to life, right there in the living room.

The other day, she was as usual on the floor, cross-legged, focused, and surrounded by the beautiful chaos she always creates.

Bricks, Legos, stuffed animals, puzzle pieces, stickers, pizza utensils, and the remnants of a half-built tower.

I watched her concentrate as she constructed a fortress for a family of dragons. She added a turret. It leaned. Collapsed.

She didn’t flinch. She examined the rubble like an engineer in training, then clapped her hands with delight:

“Ena”, (that’s what she calls me), “look, dragons need big doors.”

No complain of being wrong. No sigh. No shame.

Just discovery. Data. And another version.

I was in awe, not because the tower fell, but because she didn’t fall with it.

She didn’t take it personally. She didn’t internalize it. She simply adjusted the design and carried on.

And as I watched her begin again, fearless and laughing, I thought:

When did I stop doing that? When did I start hiding my drafts and apologizing for my ideas?

I thought of my younger self, part daydreamer, part inventor of whole worlds no one else could see, back when imagination didn’t ask for approval.

Who once built makeshift movie sets out of shoeboxes, and turned every blanket into a news studio. Who recorded fake interviews on a cassette recorder with a made-up name.

Who believed every failed idea had another version inside it.

Who wrote again, and again, and again, poems, stories, beginnings that didn’t need endings.

I don’t know exactly when she disappeared.

But I do know this: I want her back.

Because that girl, like Eva, wasn’t afraid to look silly.

She wasn’t scared to try.

She just wanted to create.

The Great Unlearning: Why We Lost Our Creative Courage

Somewhere between finger-painting and performance reviews, we were taught to stop experimenting.

We learned to chase gold stars and titles instead of wild ideas. We were rewarded for getting it right, not for daring to try.

And slowly, quietly, we absorbed the lie that being wrong is dangerous.

In his now-legendary TED Talk, Do Schools Kill Creativity?, Sir Ken Robinson argues that we are all born creative, but we are systematically educated out of it. It’s no coincidence that his talk is the most viewed TED Talk of all time. It struck a universal nerve, because deep down, many of us feel we left our creativity behind in a classroom somewhere…or maybe even earlier than that.

“If you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original.”

He believed creativity isn’t a gift for the lucky few. It’s a birthright.

But our systems, well-intentioned as they may be, often mistake standardization for intelligence, and compliance for capability.

In that talk, he told the story of a six-year-old girl in a drawing lesson.

The teacher asked her what she was drawing.

“God,” she replied.

“But nobody knows what God looks like,” the teacher said.

“They will in a minute,” the girl answered.

That kind of confidence, the audacity to create something the world hasn’t seen yet, isn’t taught. It’s innate.

And it’s often lost.

Unlike children, adults develop a fear of making mistakes, a fear that slowly replaces curiosity with caution. Sir Ken Robinson warned that this fear doesn’t just hold us back, it stifles creativity at the root. To him, recognizing and honoring our creative capacity isn’t just about artistic expression.

It’s about survival in a future we can’t yet predict.

We’re educating children for a world that doesn’t exist yet. And if we don’t protect their imagination, their flexibility, their instinct to ask “what if?”, we risk sending them into that unknown without their most essential tool.

Sir Ken Robinson was saying this long before AI began to dominate our daily lives, before we started questioning whether our imagination might be replaced, our skills made obsolete, and our jobs taken.

Now more than ever, we’re left wondering: Will emotional intelligence and creativity be the most essential skills of the future?

Robinson reminded us that we often prioritize the right answer over the brave one.

That we value conformity more than imagination. That we punish mistakes instead of honoring experimentation. And this doesn’t stop in childhood.

We carry those lessons with us, into the office, into our relationships, into our creative lives.

We avoid risks that might make us look foolish. We stay silent even when we want to speak. We don’t raise our hands. We don’t ask “why not?” We don’t say “I don’t know,” not because we’re unwilling to learn, but because we’ve been taught we’re supposed to already know.

We edit before we explore.

We stop at the first “no.”

But creativity doesn’t live in the safe zone.

It lives in the unknown. It lives in the mess. It lives in the willingness to rebuild. To iterate. To begin again. The people who stay creative aren’t the ones who never fail.

They’re the ones who keep playing in the sandbox long after the world tells them to grow up.

I think my younger self went back to building.

I, on the other hand, went back to thinking.

How could something so simple, so instinctual, become so hard for us as grown-ups?

And then I remembered that we’ve been taught to feel shame around our “oops.”

Conditioned to hide the glitch. To delete the draft. To see error not as a clue, but as a character flaw. But science tells a different story.

A story in which the mess-up is the map.

The Science of “Oops” — The Scientific Heartbeat of Creativity

Creativity and failure are neurologically linked. And the story we tell ourselves about failure shapes everything that happens next.

It’s not just philosophy. It’s physiology.

When we fail, the brain doesn’t respond to the failure itself, it responds to how we interpret it. This is known in neuroscience as cognitive appraisal: the lens through which we evaluate experiences. It determines whether our brain processes a setback as a threat to avoid or a challenge to grow through.

In other words, two people can fail in exactly the same way, and have completely different outcomes.

The first person says, “I’m not good enough.”

Immediately, the brain activates the amygdala, our fear center, triggering a cascade of stress responses.

Cortisol surges. Heart rate spikes. Focus narrows. Creativity shuts down. The brain enters survival mode, not innovation mode.

The second person says, “Interesting. That didn’t work. What next?”

Their brain responds very differently. The prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for reasoning, creativity, curiosity, and adaptability, lights up.

Instead of panic, the brain opens up. It starts solving problems. It builds new neural connections.

It learns.

It’s not failure that limits us. It’s how we frame it.

Our minds don’t actually fear failure, they fear what failure might mean about us.

In Brené Brown’s words:

“You can’t grow if you’re afraid to be seen growing.”

That one mindset shift, from fixed identity to growth, changes everything, especially in creative work.

The most innovative people don’t fail less than others. They interpret failure differently. Research on elite performers, artists, athletes, scientists, shows they are just as prone to setbacks as anyone else. The difference?

They expect failure. They extract data from it. And they try again, better informed than before.

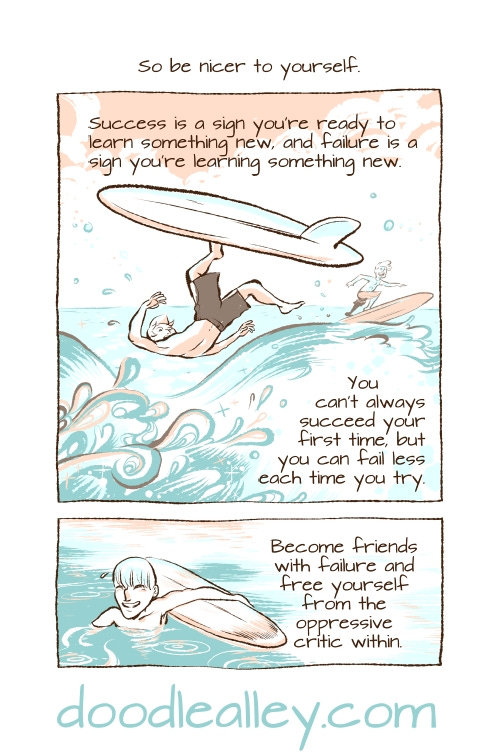

The celebrated comic artist Stephen McCranie’s reflections on creativity and failure align closely with Sir Ken Robinson’s vision: that true creative growth isn’t about chasing perfection, but about embracing the messy, often unpredictable process of becoming.

In Brick by Brick, McCranie distills this philosophy into accessible, illustrated wisdom, most notably in his essay Be Friends with Failure. He doesn’t just accept failure as part of the process, he reframes it as an essential companion on the creative path. Rather than seeing mistakes as signs of inadequacy, McCranie urges creators to treat them as data points, lessons, and even encouragement.

His work echoes Robinson’s belief that educational systems often stifle creativity by punishing failure, when in truth, failure is where learning, and growth happens. Both visionaries remind us that creativity is less about brilliance and more about resilience: the quiet courage to show up, fall short, and try again.

“The master has failed more times than the beginner has even tried.”— from Be Friends with Failure, Brick By Brick—Stephen McCranie

When failure is reframed as feedback, the brain stops bracing.

It starts building.

Why Toddlers Learn So Fast

Children don’t treat mistakes as proof that they’re incapable.

They treat them as signals, nudges from the world saying, “try another way.”

There’s even a neurological signature for it: error-related negativity (ERN). It’s a specific spike in brain activity that occurs right after we make a mistake.

Essentially, it’s the brain saying: “Oops, wait, that didn’t go as expected, let’s pay closer attention.”

And here’s what’s incredible: The brain actually becomes more engaged after a mistake, not less. Especially in children, who haven’t yet been taught to associate error with embarrassment or shame.

That’s the hidden genius of a child’s mind. They don’t fail.

They experiment.

The Bumblebee Paradox

By all known laws of physics, the bumblebee shouldn’t be able to fly.

Her wings are too small. Her body is too heavy. The math doesn’t add up.

But she flies anyway. Because she doesn’t know she’s not supposed to.

She never read the memo.

We did.

We were briefed early and often.

Follow the rules. Be realistic. Stay inside the lines.

Don’t raise your hand unless you’re sure.

Don’t share your draft unless it’s polished.

Don’t try unless success is guaranteed.

The bumblebee didn’t internalize any of that.

She simply moved forward.

So what if we unlearned what the bumblebee never learned?

What if we stopped waiting for permission to try?

What if we looked at failure not as a signal to stop, but as evidence that we’re reaching, risking, and creating something that matters?

Because I’m telling you, failure isn’t the end of the road.

It’s the entrance to the one that leads somewhere new.

Creativity Needs Room to Fail

Here’s what we know from psychology, neuroscience, and every child who’s ever built a spaceship from cardboard:

→ Mistakes are learning accelerators.

→ Brains grow by reframing failure as feedback.

→ True creativity requires psychological safety.

→ Innovation thrives where embarrassment is allowed.

Failure is our creative partner.

The only question is:

Are we willing to sit next to it, take notes, and try again?

The Five Experiments to Reignite Creative Courage

By now, we’ve unlearned a few things. We’ve made room for the mess. We’ve seen that behind every brilliant idea is a brave one that dared to fail first.

So how do we bring this into our real lives, beyond the theory, the science, the stories?

Let’s call this your Inner Mad Scientist Starter Kit.

Five gentle, playful, low-stakes ways to start showing up for your creativity, imperfectly, courageously, consistently.

1. Embrace the Prototype Mindset

Every poem, sketch, email, or idea?

Just Version 1. That’s all it ever needs to be.

Try this: Write a poem that’s purposely bad. Let it be silly. Let it breathe.

Then leave it alone. Don’t fix it. Just enjoy what it showed you.

2. Keep a “Failure Resumé”

Inspired by Princeton professor Johannes Haushofer, document your experiments.

Log what you tried, what didn’t work, and what surprised you.

Want your own copy of the Failure Resumé?

I’ve created two free templates to help you document the lessons behind what didn’t work, not as a list of regrets, but as a reflection of your growth.

→ One for entrepreneurs

→ One for professionals and creatives navigating change or reinvention

3. Rewire Your Inner Monologue

Language becomes belief. Belief shapes behavior.

Try swapping these:

“I failed.” → “I gathered insight.”

“This is embarrassing.” → “This is an experiment.”

Small words. Big rewiring.

4. Play Like a Child

Build something ridiculous.

Doodle with your non-dominant hand. Wear something weird on purpose. Doodle in the margins. Cook without a recipe. Speak up in a meeting with an idea that scares you a little. Dance outside.

Let something fail. Watch what it teaches.

Then…celebrate it.

Tell a friend. Journal it. Or share it with us here.

And remember, in the end, the people who change the world?

They’re the ones who stayed in the sandbox.

Even when it got messy.

And they kept on playing.

5. Search the Adjacent Possible

Biologist Stuart Kauffman described creativity as the act of exploring the edges of what already exists. It’s not always about giant leaps into the unknown, but about stepping just outside what we think is possible.

Pixar lives by this. Their entire creative process is built on brave beginnings, constraint-driven innovation, and the belief that every masterpiece starts as a mess.

(We’ll dive deeper into this idea, and Pixar’s Creativity Code, in the next edition: a blueprint for brave work, honest feedback, and your own “ugly first draft” playground.)

Breakthroughs often don’t come from leaping far away, but from stepping just outside the familiar.

Look for what’s nearby, but not yet explored.

That’s where possibility begins.

The sound of the second and third, and fourth click

As we wrap this chapter up, I keep thinking about that sound.

I think creativity sounds less like applause, and more like the quiet click of Legos snapping back together.

Like a turret being rebuilt just a little wider than before.

Eva doesn’t call it failure. She just calls it “what now?”

And maybe that’s what we’ve all been aching to remember: That we don’t have to be perfect to begin. We just have to be willing to hear the crash, stay in the room, and keep building.

I sometimes wonder what happened to the cassette tapes I recorded as a kid. The ones with the static-filled interviews, the made-up names, the invisible audience.

They’re probably in a shoebox somewhere, long forgotten. But the girl who made them?

She’s not gone. She’s just waiting.

Waiting for me to pick up the mic again. To try something weird. To write something risky. To remember that it doesn’t have to be polished to be powerful.

So maybe that’s the final act of creativity:

Not to impress, but to return.

To who we were, before we knew the rules.

Before we feared the fall.

Before we forgot we could build something better the second, third, fourth time around, and so on.

“The creative adult is the child who survived.” — Ursula K. Le Guin

Until next time,

Eleni

Every Monday at 11:30 CET, the Glorious Fail will meet you where you are, ready to disrupt, challenge, and rebrand failure.

There are plenty of ways to support the Glorious Fail:

→ If this landed a little too close to home, give it a like.

→ If you have thoughts, feedback, or just want to say hi, drop a comment.

→ And If it cracked something open and want to spread the word, hit that restack button below.

The Glorious Fail is just getting started, and every interaction brings it to life. Let’s fail forward, together. Rebrand failure. Reclaim the story. Rewrite what comes next.

Love this. Looks like that girl is back!!!

Creativity is the key to a fulfilled life..